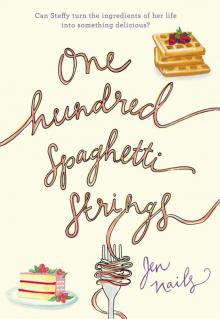

One Hundred Spaghetti Strings Read online

Dedication

For my mom, my dad, and my sister

Contents

Dedication

Making the Place Cards for Spaghetti Dinner

Chocolate Chip Banana Bread on the Flower Wreath Plate

Greasy Spoon

Unsalted Peanuts

Brussels Sprouts and Egg Whites for Din-Din

Spooky Jell-O

Marinating Chicken in an Eggy-Looking Sauce

Carrots to the Beat

Spicy Nina-ritos

Iced Caramellatos and Bubble Tape

Crock-Pot Thanksgiving with the Blue-Stained Hand Guys and Cigarette Carol

Kitchen Sink

Fully Cooked

Something Big at Sausage-and-Pepper Night

Gnocchi with Nina

Coffee and Sauce

More Ginger Ale, Anyone?

Farm-to-Table

The Great Cupcake Burst

Getting My Hands in a Recipe

When She Wrote the Recipes Down

Potatoes and Yams and Bears, Oh My

Dozens of Dinners and Desserts

Chef of Today

A Thing of Pizza Dough

Shaking on the Sugar

The Donation Pie

The Cream-Puff Flash

Sauce and Stew Meat and Down the Stairs

The Berries Keep Spinning and Spinning

Breakfast for Dinner

The Good News Potpie Meal

Jeannie Beannie’s Lemon Bars

Keep Cooking, Hot Stuff

Just Lemon Water

It’s Time for Chicken Parmesan

How to Make Cinnamon Rolls

The Cupboard Is Bare

Hungry

Parsley

Snacks in Bed

Cheerios and Toast for Dinner

The Water’s Boiling

Roasting Marshmallows

Getting Excited Again about Being a Chef

Tummy Ticklers for Little Tots

Hi, James Falcon, I’m Gonna Be Doing Cooking Lessons.

Cake, Cake, Cake, Cake, Cake, and Cake. And Candy. And Cookies.

The Biggest Cleesh

Hands to Heart to Handwriting

Birthday Cupcakes

Having Some Tea

Bread Crumbs

Kitchen Sink Cookbook: A Year in Recipes

One Hundred Thank-Yous

About the Author

Praise

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Making the Place Cards for Spaghetti Dinner

My dad was coming back home. He had been gone for two years playing music in California. And before that he lived here in Greensboro, in an apartment that we were never invited to on Cumberland—at the end of Cumberland—and we only saw him about once a month if that. And before that it was kind of blurry, like when you think you have a memory of eating green Popsicles with your sister on the porch steps with no grown-up around but then you think maybe someone told you that they once ate green Popsicles with their sister on the porch with no grown-up around.

I decided on the pink dress that used to be Nina’s but she never even wore it—she was going through a black phase—and so I had torn off the tag with my teeth. It looked okay on me except 1) the chest part was itchy, and 2) it was kind of too short, and 3) I was worried about my dad coming, so there was an “except” to everything that night.

A car door slammed and the neighbors’ Doberman pinschers barked and howled. Instead of going downstairs I stayed in my bedroom and grabbed Wiley, my green dog.

I heard the front door opening and Auntie Gina saying, “Hi, James,” and then my dad’s deep voice saying something I couldn’t make out. Then a pause, and then her saying, “Come on in.” I squeezed Wiley around the middle. In the two years, we had only talked to Dad on the phone one time. Christmas, when I was nine. Now I was eleven, starting fifth grade tomorrow, and I was kind of a whole new person. I was reading longer books, I could ride my bike with no hands, and I was allowed to cook and bake all by myself, turning the oven on and everything.

I tossed Wiley back onto the bed and wiped my eyes with the backs of my fingers. Dad was here. And he was staying. My fingers still had onion smell on them from when we were cutting up all the stuff for the sauce this morning, and now, wiping my cheeks, I got that burning in my eyes again.

There was a bang bang bang on my door.

“Steffy,” my sister, Nina, said.

My face was puffy and I knew it, and I opened the door to Nina’s puffy face, and we gave each other a look where you knew the person had been crying but they didn’t say anything so you didn’t say anything.

“Come on,” she said. She tramped down the stairs ahead of me. I wanted to stay in my room. Forever. But then I wanted to go down more than anything else in the world. I held the railing tight. The wooden steps felt extra hard under my bare feet.

Down in the kitchen, Auntie Gina and her boyfriend, Harry, sat facing us at the table. I don’t know when she had time—between making dinner and now—but Auntie Gina had taken a shower, and her thick, curly brown hair was still damp. She wore her green “hangin’ around” dress, as she called it, and of course all her funky bracelets. Harry was this tall Korean guy who Auntie Gina met in college and had been with her ever since. He had on my Spud Stud apron, and he winked at me when he saw me. And sitting on the other side of the table, with his back to us, was my dad.

“Girls,” said Auntie Gina, “say hi and welcome to your dad.”

“Hi and welcome to your dad,” said Nina, crossing her arms.

“Hi,” I said, waving.

“Hey,” he said, turning around and standing up. He put up his hand and covered his mouth. Were his eyes kind of watering? They were a little glassy. I wondered if we should hug him, but he didn’t go to hug us so I stood still, a little behind Nina. I grabbed a piece of the elastic-y material on the chest part of the dress and moved it back and forth. I peeked down and saw I was making a red mark there, but I just had to scratch.

My dad had Auntie Gina’s keys in his hands.

They were his keys now. And this was his house now, and we were supposed to be his daughters. Having him there holding those keys and then seeing all the suitcases and bags and backpacks and plastic sacks by the front door bulging with Auntie Gina’s stuff was forcing me to admit that it was all happening.

Our auntie Gina was moving out.

She had taught me to read. She got me cooking and baking. She had stayed awake with me when I was scared.

Taking his hand from his face, my dad said, “You’ve both gotten so tall.” He shook his head. “My girls.”

Nina said, “Ha.”

Yeah, we are your girls, I wanted to say. We’ve always been.

“Nina, look at you,” he said. Yeah, everyone looked at Nina, always. Boys in the grocery store turned around to get a second look. Sometimes older guys, too. This always made Auntie Gina put her arm around Nina and walk faster. Even the person in the car next to us would do a double take. Nina was an I-don’t-even-wear-that-much-makeup girl. Dark-blue eyes and a wide smile and thick, dirty-blond hair. But she didn’t care that she was pretty, and she didn’t act like she wanted everyone to notice her.

Wow, I thought as I looked at them looking at each other. A mirror. She’d be as tall as our dad, maybe, in a few years. They had the same hair. And a little swagger—this kind of swaying thing like they both heard their own music and kind of moved along to it.

“And Steffy,” he said. “Little Steffy.” There was something in his eyes that drew me right in, and I could have sat right down and told him and asked him everything. Why are you here, will you

stay, do you love me, what do you want me to be, do you remember tickling us on the green chair?

Instead, Nina said, “This is fun.”

“Well, James,” said Harry, Auntie Gina’s boyfriend, pushing back his chair and standing up, “come on up and we’ll get you settled.”

While Harry picked up our dad’s duffel bag and briefcase and walked him upstairs to Auntie Gina’s room (his new room), I set out the place cards I had made last night. All the drawings I’d done on them seemed babyish and stupid right then, but Auntie Gina made me put them out anyway. It had felt weird writing the word Dad on a place card, like he was a character in a play or something. Not a real person. I put “Dad” across from me and Nina, and Harry and Gina at the heads of the table.

“So, this is, like, really happening?” Nina asked as she set the bowl of tomato sauce on the table.

Auntie Gina laid down the knife she was using to slice the garlic bread and said in a whisper, “Nina, he’s the only daddy you’ve got. Plus, he’s got rights I don’t have. It’s time you girls had him back.”

“No,” said Nina, “it’s time us girls had a choice in the matter. Right, Steffy?”

“I don’t know,” I said. I didn’t. Nobody had ever really said that we could choose what we wanted to have happen to us.

We put down the rest of the dinner stuff, and the smell of the sauce that had been simmering since sunrise calmed me down. When we made Italian food, this house seemed more like home than ever. It had always been my mom’s specialty. But I couldn’t imagine eating anything. My stomach felt like it was full of bedsprings and someone was jumping on that bed.

Auntie Gina had lived with us since my mom’s accident when I was three. It was another foggy memory where Grandpa Falcon (my dad’s dad) came into the living room while Nina and I were eating apple slices with the peeling off and watching Dora, and he said our mom got hurt in the car accident and that she was in the hospital. He didn’t turn off the TV while he told us, and when he finished, we kept watching. Since then our mom’s lived at the Place and gets taken care of by her nurse, Helen. I don’t really remember her anywhere but there.

Dinner with everyone was like watching a movie. I didn’t feel like I was really part of it. All I know is I kept pulling the elastic on my dress back and forth across my chest, digging into the itch. There were a lot of fork clinks and chewing and swallowing noises. Harry told Dad a story about taking his car to the mechanic. I didn’t have anything to say about getting your oil changed, so I could kind of just be in my own head, sneaking looks at my dad.

Noticing his long fingers around the fork, his mouth when he chewed. Feelings all jumbling around inside of me. I wished I were chopping the onion for the sauce right then, like I did this morning, so there would be an excuse for me wiping my nose all the time. Then Auntie Gina was saying things to bring me back to the table.

“So, the girls’ll ride their bikes to school after you get your bus to work,” she said to Dad. “And Nina has dance after school on Mondays, Tuesdays, and Thursdays—it’s a confusing schedule—and Stef comes home alone on her bike.”

Auntie Gina nodded at me. “Also, you’ll need plenty of groceries in the house,” she said. “We’ve got a budding Julia Child on our hands here. I guess the two of you can take the bus to the Harris Teeter each week, James. . . .”

I glanced shyly at my dad, who was spooning sauce onto his second helping of pasta. I wondered what sitting on the bus next to him would be like. I wondered what we’d talk about. I hoped I’d be able to think of something to say.

I managed some sweet tea and a few bites of spaghetti and one meatball. I had helped roll out the dough and turn the crank on the pasta maker, catching the noodles as they slid down my palm.

After everyone finished eating, I helped Auntie Gina put dishes in the dishwasher, and she made Nina go load sacks and backpacks into Harry’s car. My dad and Harry sat in the living room talking about man things. Harry could talk to anyone about anything. He was always asking people about themselves and then bringing up more things about what they said. He reminded me of the big, green easy chair that used to be at my Grandpa Falcon’s—worn in and comfy, and it would always hold you. Maybe my dad would end up being something like that.

After Harry had gone home and my dad was up in his new room, I went and changed out of the dress and into my pajamas. It didn’t feel right that he was in that room two doors away. It didn’t feel right that Auntie Gina was setting up a blanket on the couch. She’d sleep over that night to help get everyone settled, but nothing felt settled at all.

My whole chest was burned with all the scratching, and the coolness of a big Greensboro Grasshoppers T-shirt was a relief. I went downstairs to say good night to Auntie Gina again. Her and Nina were on the couch, and when they saw me, they stopped talking. Auntie Gina leaned in and kissed Nina’s cheek, and then my sister hurried up the stairs, her arms crossed in front of her.

Auntie Gina and I were quiet. There wasn’t really anything more to say about it. We stood up for a big hug, and I breathed in her pear lotion.

“I love you, Steffany. And I know you’re going to be just fine,” she whispered. Her silver bracelets clanged together as she grabbed me closer.

I didn’t feel just fine. I felt like that long, wide piece of dough traveling through the pasta maker, coming out a hundred spaghettis. Before this night, there was Auntie Gina, always asking us if we did our homework, always letting me make messes in the kitchen, always there to pick up Nina from dance. Before this night, it was all Auntie Gina. Now she was leaving, our dad was staying, and I felt like I would never be whole again.

Chocolate Chip Banana Bread on the Flower Wreath Plate

There were tons of handwritten and newspaper-torn-out recipes spilling from my mom’s old Better Homes and Gardens cookbook, and the banana bread one was stained with cooking oil and felt like cloth between my fingers. Each of her recipes always got me imagining her writing down the ingredients and wondering why she liked it, where she got it, when was the first time she made it. Auntie Gina might know or, if not, the answers were stuck somewhere in my mom.

While I mixed the wet ingredients (eggs) with the dry ingredients (flour, salt, and baking soda), I thought about how I was half Sandolini (my mom’s side) and half Falcon (my dad’s). How it was like me and Nina were the eggs and Dad was the flour. How Auntie Gina had just dumped us all into the bowl together without mixing us up with her wooden spoon.

When Dad left for California, Nina started saying her name was Nina Sandolini instead of Nina Falcon. Auntie Gina didn’t say she couldn’t. And then I started doing it, too. I liked having an “S” first name and an “S” last name. Pretty soon teachers started calling us Sandolinis instead of Falcons. I always wondered if they talked to Auntie Gina about it, but I never asked. Now that Dad was back, I hoped he wouldn’t be mad that his last name was missing from my signature.

I had everything ready for him for when he came down. His piece of banana bread was on one of the nice plates with flower wreaths, and my piece was on a paper plate.

Dad said, “Hey,” and I said, “Hey.” He poured himself a cup of coffee and then said he was going outside to get the newspaper. I sat perfectly still, maybe I didn’t even breathe. I hoped he’d like his breakfast. When he got back in with the paper, he sat down in the chair that didn’t have banana bread in front of it. I reached across the table and slid the plate in front of him.

“Oh, no thanks,” he said, opening the paper. “I’m not a big breakfast guy.”

The pictures in my head of him loving the moist, fresh-baked bread, and of me showing him Mom’s old recipe, and then him telling me about a time she made this banana bread for him—those pictures went away, and I wanted to go get under my covers with Wiley. It felt really dumb to eat banana bread by myself. But it smelled so good that I did anyway.

Nina came down in a black tank top and purple shorts. She took one of her earphones out and a song with ma

racas and drums blasted from it.

She said, “I need a new combination lock for my bike.”

“I can bring you one tonight,” said Dad.

“Can’t you just give me money and I’ll get one after school?”

He reached into his pocket and came out with a folded wad of money. He put five dollars on the table in front of her and five dollars in front of me. “Go to Hal’s on Huntington,” he said. “He won’t rip you off.”

I could tell Nina wasn’t expecting him to just up and give her money. I could tell she was trying to pick a fight. “Um, Dad, Hal got sick and closed that place like two years ago.”

“Really,” said Dad.

“Yeah. So, like, what’s your job exactly?” she asked.

“Painting an apartment complex.”

“Sounds stimulating,” she said.

Dad put down his mug. “I wouldn’t call it that, but I’d call it work.”

“New for you, huh, Dad?”

“What?”

“Work.”

“All right, Nina, let’s get started off on the right foot.”

“I’m on the right foot, Dad. I’m always on the right foot. So, like, you came back here to paint an apartment complex?”

“I came back home, Nina, is all. All right? I just needed to come back home.”

She slapped her hand on the money and slid it off the table. Then she reached over, snatched Dad’s banana bread, and headed upstairs. “This looks awesome, Steffy, thank you,” she said. In a minute her bedroom door slammed. The whole time, the newspaper stayed up in Dad’s face. I coughed because it was so quiet with us just sitting there.

He got up and put his mug in the sink. I wondered if he was noticing the picture of Mom, her high school senior picture that Auntie Gina had hung up a long time ago next to the window above the kitchen sink. She’s in a tank top dress, and her wavy brown hair is all down at her shoulders, like mine, and her brown eyes are shining at the camera, and her mouth is open in a smile like she just heard something funny. If my dad was noticing, he wasn’t saying anything.

I thanked him for the five dollars. He told me to have a great first day of fifth grade, and I said I would. He called up, “Bye, Nina,” and she yelled down, “Bye.” He told me to remember to lock the door behind me and then he was gone. We had never done this—the thing where the grown-up leaves first. I wondered what box Auntie Gina was unpacking over at Harry’s right then.

One Hundred Spaghetti Strings

One Hundred Spaghetti Strings